Rural – Jersey Country Life Magazine

What’s for Dinner?

Introduction

The Macro Themes

Farming – What Sort?

Something To Eat

Food and Farming in Jersey – New Models

The Natural Environment

Postscript to ‘What’s for Dinner?’

What is Permaculture?

By Graham Bell

The starting point for the question: ‘What is Permaculture?’ is that it is our prime duty to care for our children and our families. If we don’t, who will?

We understand that blaming some other entity for the challenges of living is to ignore our responsibility and to abrogate our power to others. I see it like the layers of an onion, that as we move outwards from our core responsibility we also accept the need to care for our neighbours, friends and even people we don’t know. Permaculture is first and foremost about people, and providing for all human needs.

We cannot achieve these goals without caring for our natural environment. This includes being conservative about how we use energy. Climate change and a burgeoning world population amplify the importance of this realisation. Money is a key issue across the planet, both in terms of the affordability of public services and the differences between rich and poor. Jersey’s wealth as a major financial centre is self-evident. Within our movement we have a deep commitment to helping those in need. The state of the world is of concern internationally for many reasons, including political, climatic, social, migration and conflict as well as the acceleration of species extinction.

Permaculture

Permaculture is a systematic methodology for better designing how we supply human needs, whilst leaving the planet at least as productive as we found it and preferably more so. Conservation is no longer enough. We need regeneration and the discipline supplies the tools for slow and considered actions to replace thoughtless haste in our increasingly consumptive habits.

Two key objectives are the elimination of waste (pollution) and the reduction in work. Another definition has been ‘revolution disguised as organic gardening’. Gardening is not a bad place to start, for gardening exemplfies the production low intervention bountiful systems. It is good for mental health, gentle exercise and relatively harmless. Ghandi’s use of the Hindi word ‘Ahimsa’ is usually translated as non-violence. I prefer harmlessness as a better translation. Not a bad aspiration to have in the present day.

Another dimension is to consider closing energy loops, so all our outputs become reused as our inputs. The truth of that matter is there are no perfect Permaculture systems anywhere on planet Earth. It is a direction not a destination, constantly looking to reduce work and waste and to improve yield. You might just say it’s common sense that isn’t common enough. I have always said we are not missionaries – there is plenty to do working with people who want to know not to worry about those who don’t. Added to this, if good change is slow, we really need a steady hand on the tiller as we sail into an unknown future. As I get older, I worry about whether we have enough time to change our global direction before it is too late.

In teaching Permaculture (and over two million people plus have done a course worldwide to date) we share three key ethics: people care, Earth care and fair shares. The first is clearly our original intention, but we cannot care for ourselves if we destroy the planet’s habitats, and we seek to minimise inequality whilst setting limits to growth. We must all be crucially aware there is no Planet B.

The American ecologist Aldo Leopold wrote: ‘We abuse land because we regard it as a commodity belonging to us. When we see land as a community to which we belong we may begin to use it with love and respect.’

Good change

Ken Gilbert taught: ‘The mechanics of industry are easy. The real engine is the people, their motivation and direction.’ So how can we influence good change and what is needed?

Poverty charity Oxfam suggests that a mere 85 people own as much as the poorest 50 per cent of the world’s population (three billion and rising). It is said the disparity is increasing. Voltaire’s remark ‘The comfort of the rich depends on an abundant supply of the poor’ writ large.

To help us on our way there also many examples of great beauty, natural abundance and loving kindness in the world. One of the things we don’t do enough of in the world is nothing (masterly inactivity in the Buddhist expression). ‘Being…’ we call ourselves ‘human beings’, but it is truer to describe ourselves as ‘human doing too much of the time, rushing around and forgetting just how to be.’

Replacing impetuous action with long and protracted thoughtfulness can massively reduce our global impact and create a better environment for all life.

Permaculture teaches a set of principles to aid us in applying solutions, the first of which is ‘observe and interact’. Before doing anything we learn to stop and notice. For example, we have taught our grandson from an early age the edible plants in the garden. He loves to pick soft fruit and Sweet Cicely (Myrrhis odorata) in the garden and enjoys them as ‘sweeties’ free from artificial sugars.

When I was growing up in the 1950’s we spent most of our free time in the garden or exploring the countryside. Our garden is due east of Alaska, due west of Moscow and produces 1.25 metric tonnes of food a year, 500 trees and 5,000 plants for sale and attracts a thousand visitors annually. It measures 800 sq metres (a fifth of an acre in imperial measurement). The food alone is at the rate of 16 tonnes a hectare, more than twice the most productive chemical farms around us on grade one agricultural land – for all their John Deere tractors and carbon dependency. It does require hand labour- but meaningful work is in short supply globally. All of that is managed on about two days a week (maybe more at peak harvest time). It is pretty much self-fertile taking very few external inputs.

Catch and store energy

Our second principle is ‘catch and store energy’. The bulk of our harvest comes between June and October, so we spend a great deal of thought and some energy on storing food through a wide range of preservation techniques. A key element in this principle is our trees. We only need one nuclear power station – the Sun. And tree leaves are the best solar panels we have. The beauty of our food forest is not just in the seeing of them, but in their bountiful harvest and their contribution to chemical free soil fertility.

We practice thinking in five dimensions- the two of horizontal space, and the third vertical dimension, so neglected by broad-scale chemical farmers who pour soluble chemicals onto the soil and consequently pollute the water table, killing the life in the soil, paying little attention to trees. The fourth dimension is time and the fifth is relationships. In this vibrant polyculture everything is feeding everything else. Pest control is largely designed out.

Our third principle is to obtain a yield. We are certainly doing that. Apart from the produce (where we share our surplus) there are also important human yields. Learning, interaction with like-minded others and a sense of peace and harmony all score highly. It also provides us with a soft living space supporting 37 species of nesting birds and 40 more which visit, as well as a population of two tonnes of earthworms. That’s not forgetting all our firewood and half our electricity from solar panels. All of this is 6 degrees nearer the pole than the Channel Islands.

Principle four is ‘apply regulation and accept feedback’. We do these two things by weighing all our yields to within 100g and interacting with our visitors and scientific researchers. It has taken 30 years to achieve this level of fertility and we do have occasional help from interns and friends.

The Czech poet Karol Capek said: ‘I find that a real gardener is not a person who cultivates flowers, but one who cultivates the soil.’ For me this is the key distinction between chemical free farming and industrial agriculture – it is imperative that we move from feeding plants to feeding the soil. We can only survive a few minutes without breathable air, a few days without potable water – but civilisation cannot last without topsoil.

Libya was the breadbasket of the Roman empire, Syria a forest kingdom in historical memory; the Tigris/Euphrates delta was the birthplace of West European agriculture and all are now massively desertified. The soil losses in the USA would fill a train annually going 14 times round planet Earth. Soil lost to our oceans takes millions of years to recover. The soils we have in Britain took 10,000 years to build since the last ice age. In some places we are losing them in a single storm, but nationally they are degrading incrementally.

Our strategies for building topsoil are:

- No bare soil- mulch or replant as soon as possible after harvesting

- Maximise polyculture: flowers, herbs, salads, weeds (many are edible), vegetables, soft fruit, tree fruit and nuts

- Know your species – don’t stop learning

- Minimise tillage which can destroy soil structure

- Allow life – welcome wildlife

- Create the right habitat and the right things will happen

We use leguminous plants as much as possible to attract nitrogen fixing bacteria, and help young bees develop body mass through their protein-rich pollen. Together all these strategies encourage earthworms and fungi and they build resistance to both heavy rain and drought; we harvest all the rainwater we can.

A fifth principle is to use and value renewable resources and services. We save our own seeds, propagate plants and trees, make 15 cubic metres of compost annually, refit our house to be more energy efficient, minimise household waste and reuse or recycle 90% of what we do use. This ties into a sixth principle: ‘produce no waste’.

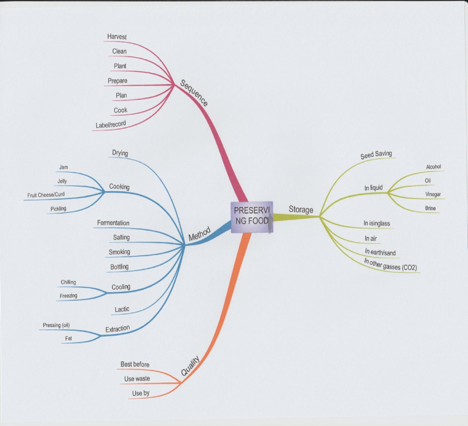

The seventh principle is illustrated by this mind map and gives an example for food preservation.

Our eighth principle is: ‘integrate rather than segregate’. So, polyculture rather than monoculture would be an example in practice. We have already touched on a ninth principle: ‘use small and slow solutions’, and a tenth principle: ‘use and value diversity’. The following table is a prime example also:

Penultimately: ‘use and value edge and value the marginal’. This is based on the ecological understanding that the overlap between different systems is both high yielding and a risk point for energy losses.

Lastly: ‘creatively use and respond to change’ is for me amply demonstrated in Socrates quotation: ‘The secret of change is to focus all of your energy not on fighting the old, but on building the new.’

And that is just what Permaculture is trying to do

It is not, however, a solution to see farmers as the enemy. We need to be grateful to the nation’s farmers for some great achievements. They are guardians of the greater part of our countryside. We need them to do that job well. Between 1945 and 1975 they doubled Britain’s food production. And they did so with a workforce that was reduced by 90%. But the challenge was met at a cost: specifically, an eight-fold increase in carbon usage on farm. And that was before the massive increase in fossil fuels in creating the chemicals used. With peak oil on the way this is clearly not sustainable.

An agricultural equipment salesman at the Royal Highland Show told me that he first sold a tractor on credit in 1955 and last sold one for cash in 1975. John Deere tractors start at a quarter of a million pounds. Our farmers are buried in debt. It is no wonder that worldwide farming now has the highest suicide rate of any profession. Farms increase in scale as smaller enterprise can no longer survive. We need to change how we grow our food, and the expectations of shoppers to return sanity to one of our most essential sectors- the production, distribution and consumption of food.

We need that change to start broad-scale. And we need to support our local farmers in making it possible. Now.