Rural – Jersey Country Life Magazine

What’s for Dinner?

Introduction

The Macro Themes

Farming – What Sort?

Something To Eat

Food and Farming in Jersey – New Models

The Natural Environment

Postscript to ‘What’s for Dinner?’

Share Farming

By James Odgers

I feel I am the least likely person to help on the subject of ‘Share Farming’. I feel I have jumped from job to job all my adult life as a jack of all trades and master of none and ended up, to my absolute amazement, as a start-up farmer with a premium brand, Stream Farm, in a hidden valley in the Quantock Hills that is now pretty well-known in the South West of England. And I look around at all the other farmers even today after 16 years at it and I feel like a babe-in arms! So, treat anything that I say about farming with a pinch of salt!

When we arrived at the farm in 2002 from London, we had bought it lock, stock and barrel. I have never discovered what the lock and the barrel were meant to be, but the stock comprised 25 tiny Dexter cows and 27 Hampshire Down sheep. We had no farming background; there was no farming in our blood; and, truth to tell, I really have very little interest in farming as such at all, as you will discover!

The day before we completed the purchase of the farm, my wife, Henrietta, spent the day with the lady of the house, whilst I walked round the farm with the husband and a Dictaphone and a clip board writing and taping everything he said in case it would be useful the following day!

I so remember looking out of our bedroom window that first morning with Henrietta and seeing these 52 animals for which we were suddenly entirely responsible and frankly, we hardly knew which were which – and we spent the first two months trying to keep them in the fields that we had just returned them to as the fences were almost non-existent – and our animal-handling skills, until then, had been limited to our children’s hamsters, guinea pigs and rabbits.

Sheep, as many readers will doubtless know, have a death wish anyway and are known for their desire to go off into someone else’s field whenever they possibly can and die there, hidden under some hedge. And we had always thought they were meant to be quite stupid. But on our first day, we watched in amazement as an old ewe took two young rams round the back of a shed in their field, clearly giving them instructions. When they emerged, the rams wriggled halfway under a loose barbed-wire fence, about three feet apart, and then stood up to make a tunnel through which the whole flock escaped – again!

And we had an early lesson in sheep parables with which we could now easily fill a book: one of the sheep was stuck in a hedge unable to move for brambles in its fleece and, as we went to help, we noticed that the rest of the flock had ignored its plight entirely and were in the lushest part of the field, a long way away with their backs to the one stuck by itself!

A journey towards farming

Anyway, I had better start a bit further back as the model and experiment of Stream Farm inevitably reflect, whether we like it or not, not just the character of the creators, or of the ones carrying it on, but also our experiences, what we have seen, what we have done, what we have been taught. And in my case, my journey towards farming is as important in many ways, as my experience of actually doing it.

I was a lawyer, for seven years, at one of the big six City firms, specialising quite quickly in investigating international bank fraud. I travelled the world looking at the different laws thrown up by different countries.

Somewhere during that time, another lawyer challenged me to investigate the claims of the Christian faith and I did so and to my utter amazement after a forensic examination of the available facts over about three years, I discovered that the evidence was incontrovertibly true. As C.S Lewis described his conversion in 1929: ‘I was the most dejected and reluctant convert in all England’.

And so that changed everything really from then on. I left the law in 1987 to do something I reckoned would be more exciting – working in the rehabilitation of drug addicts and prostitutes in Hong Kong, which I did for a while and which my family has often done since then.

I had a clear sense after a while out there though, a calling perhaps, if you will forgive me using such an old-fashioned-sounding (but nonetheless true) term, that I should return to the UK but as a banker. I had thought I had left the strange tribe of the bowler-hatted, the furled umbrella and the FT forever. I could not imagine that I was employable in that field – I am not numerate – but then it transpired that no other bankers are either! So I started a sort of a bank with some friends which floated on the stock exchange five years later and which, the moment I left it, became very big indeed – and the share price shot up when I announced my resignation!

But I was never interested in banking as such but rather in understanding how companies and their manufacturing processes work. I am always hugely impressed by people who have established a successful process of adding value, a successful and lasting brand, a worthwhile product, and I learned a lot during those years, sitting on the boards of companies across the UK and Europe, both public and private.

I left to learn about microfinance – providing very small loans to those in need in urban and rural areas to get their businesses up and running – because the modern economy seems to have forgotten that everyone on the planet needs a living if they are to survive.

The Luddites and what they foresaw

I soon saw that wage employment, made most popular after the new technologies of the Industrial Revolution in this country, was firmly kept in the hands of those who already had access to capital or land – and is not the best way to go about things. It is a model that we then shipped all over the world. Of course, this approach to economic activity was helped along in earlier years by the Enclosure Acts and the Scottish clearances – or, one might go even further back to my reputed ancestor, Watt Tyler, of the Peasants Revolt in the 14th century! The Luddites are amongst my heroes – who saw that the new technologies would lead to the break-up of their village communities – as they did – and who did what they could to stop that happening. As they stood at the gallows, they sought forgiveness from anyone whom they had hurt.

And the trouble with wage employment is that it leads to fear on a grand scale, to those deciding our destiny often being very distant, to human beings just being line items in a profit and loss account, to the needs of specific employees being unknown to the wage payers, to community breakdown on a huge scale: if all I have are these [my hands], then I must go wherever the work is – e.g in China, 400m people are said to have been raised up out of poverty but that is 400m families broken up for ever and many millions of communities decimated – and the whole story there has been fuelled by unsustainable levels of debt. That was what the Luddites foresaw.

And we are seeing today more and more power in the hands of fewer and fewer people, such as the boards of the 60,000 multinationals. Who appointed their all-powerful directors after all in the grand scheme of things and to whom are they accountable? The shareholders are mostly collective investment schemes of a variety of sorts so there is little real accountability there and anyway, if a company is so big that the chap at the top does not know the names of the wives and children of the ones at the bottom and does not know the context of the lives of those around their factories, it must inevitably lead to systemic injustice. And we are seeing CEO pay at 145 times that of their average employees. And yet, even though millennials, in particular, are so against the giant corporation – more so (because they have had no direct experience of anything else) than of red-blooded socialism in a recent survey – the thrust of untrammeled capitalism is always towards growth, endless growth, as if we have forgotten that growth can be malignant as well as beneficial.

Access to capital

So off I went to spend time with Mohammed Yunus at Grameen Bank – a magnificent microfinance outfit in Bangladesh – eager to assist the poor by lending them small amounts of money to get their businesses going. He taught me that if the poor had access to capital there would be no wage employment, no one would be prepared to work for other people if they could avoid it.

As Yunus says: ‘if labour had access to capital… wage employment would only come into the picture as an alternative to self-employment. The more self-employment became attractive… the more difficult it would be to attract people for wage jobs’. Or, as Zygmunt Bauman, the extraordinary Polish sociologist, said: ‘[wage employment should only ever be] the means to get rid of the repulsive necessity to work for others.’

He also told me that failure to repay a loan is always the lender’s fault as he has not set the terms of the loan to suit the borrower’s priorities. That was a hard one for a commercial banker to hear!

So I began to develop a different approach: to establish large numbers of small businesses with the dignity for all of ownership, rather than small numbers of large with many employees. The aim is to marshal Burke’s small platoons.

Amazingly in the FT way back then, a commentator wrote: ‘The only real protection from the economic forces of globalization and technology lies in making workers into owners.’

So after 18 months of research in the poorest parts of the world with my young family, I determined that an alternative approach would consist of a tapestry of interwoven businesses, small, family scale, local, trading with each other, with the common good in mind, with all the businesses based on trustworthiness and integrity and with the environment being well stewarded. Parts of this approach are not new thinking – the Japanese car industry was based on such lines until very recently and that shows that scale can be achieved by large numbers of small. Thus I set out to build an alternative economy and part of that involved building a brand, Stream Farm.

Branding

A brand to me means what it used to mean – the root of the word, of course, is ‘to burn’ and comes from a German origin. In order to bring about the popular acceptance of an idea, be it in economic activity or in politics, one needs to start a brush fire, something that spreads rapidly, that burns its way onto the consciousness of others, perhaps reaching a tipping point or going viral in modern parlance. There must be passion behind it and an overarching vision for what one wants to achieve. And then it needs years of perseverance and vigilance. And I have found that it is always wise to start very small so that my mistakes can be made on a small canvas first.

So I first began a microfinance lending business in Brixton in South London for single mums and widows from the African and Caribbean communities there, communities treated almost as a matter of course as a nuisance by those around them.

Most of the microbusinesses were in textiles or food – over 15 years, we trained up some 800 women, and started many hundreds of small businesses, with thousands of small loans, all repaid in full although we had no legally-binding agreements – because we trusted them to repay.

Another element of the same thinking was to start a rural project along similar lines but profit-earning – or at least not loss-making (or so we hope!) – that focuses on seeing how many traditional farming businesses or livelihoods an area of farmland can generate and still break even – and without subsidies, for we shall be living soon in a post-Brexit environment – and with each business on the farm earning enough for a family of four at a level of income somewhat above the Somerset average, or at a level that meets their needs.

Stream Farm

And that is why we bought Stream Farm in Somerset. There we have started to date some nine, pretty traditional farming businesses. The 25 cows are now a herd of about 70 breeding cows, the 27 sheep are now a flock of 275 breeding ewes. We have a rainbow trout farm that produces fresh and smoked rainbow trout to order, based on the eponymous stream of Stream Farm, smoked in a caravan we bought on E-bay for £100 and stripped out (the world’s first mobile smokery!). We planted an apple orchard in 2007 that produces a delicious juice; there are table birds, chickens, still and sparkling water from a spring we discovered under a Victorian rubbish dump, the beginnings of a herd of pedigree pigs, a honey bee start up, an egg business and we are considering moving into crayfish and, possibly, bread. We have about six families on the farm at any given time and are heading for ten, I hope, on an area of 250 acres which received wisdom would suggest was enough land of our sort for half a livelihood.

Our neighbouring farmers initially took quite a dim view of us, thinking (quite reasonably) that we were yuppies just down for the fun of it. But then they saw my wife and I shovelling cow poo every day for several long winters and their attitude slowly changed even if they could see that we hadn’t a clue what we were doing in those early years.

As a child of the Silent Spring, I also saw a fundamental need for us to go organic, which we have been these last 15 years or so in spite of the certification costs. The demands, as I see it, of the supermarkets have compelled the farming ‘industry’ writ large to use ever more chemical inputs, fertilizers and sprays and ever more intensive livestock-rearing methodologies in search of an ever more elusive profitability; at the same time the industry has tried to address the environmental issues created by these unnatural practices by setting land aside and by procuring subsidies however they can from stewardship schemes.

Our land had been farmed commercially by a tenant before we came to it and it took some four to five years really to begin to see the soil become richer again and more alive with worms, birds and the hare. I did have to do quite a bit of sub-soiling and mustard drilling, though, and we do not yet have hedgehogs.

I so remember going out into the fields with a commercial farm agronomist that first year. We were kitted out in white boots, white overalls, a white facemask and white gloves and we carried a tin of chemicals with a skull and crossbones on it. We were to spread it on a field. As if that could not possibly be harmful to the health of those who were to eat any produce made with that wheat.

And yet 97% of farmers in England have not taken the organic route yet.

Three core values

We have emphasized that our three core public-facing values are: local, traceable and, increasingly, health – and our website covers these aspects in some detail – but there are three other elements to the business methodology that mark us out as being different, that underpin, if you like, who we are and what we stand for:

First, we do not sell to the supermarkets, the multiple retailers, who have stripped the profit out of farming and have thus caused the so-rapid decline in the rural economies that we see around us in England. We deliver for free to our markets in Bristol and Bath, Taunton and Bridgwater, to compete with the convenience of the supermarket but our prices on many of our products are less than the equivalent in the supermarkets anyway because we do not have their overheads.

Every superstore opening leads to the net loss of 224 jobs – often, if not usually, jobs long-rooted in the local community and replacing them with cash tills that will increasingly be automated. Every superstore has prices about 12% above their equivalent in a local retailer and their town centre outlets often have prices some 30% higher. They have won the consumers’ hearts and minds and are over-charging them in the name of cheap food!

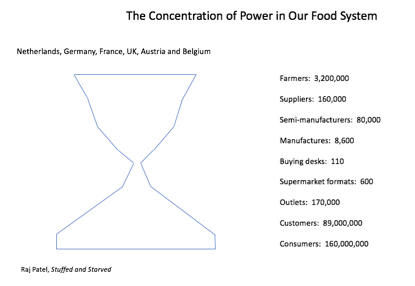

Here is a very rough diagram that should be etched in our minds as it describes the key problem facing today’s farmers in England – more important than Brexit, when only 6.7% of all food producers in England export anything, more important than subsidies, more important than the rapid rise of very fashionable vegetarianism, more important than the need to explain why all of us need to eat a lot more high quality red meat and fish than we do for a balanced diet and more important than the advent of large scale mechanization and other industrial practices. Oh how the rot set in when we began to view farming as an industry!

My focus for some time now on the political front has been to try to persuade them to take an axe to the supermarket chains – just as we did with the brewing companies a while ago and their tied estates and, in America, with the railroad barons and the telecommunications oligopoly.

Secondly, every farming family that comes on to the land takes on and owns one of the businesses, alongside us, for a couple of years under a share farming agreement while they learn the ropes. So, share farming means that we share gross receipts, not profits, we are not a partnership, and the farmer takes enough, first, for a livelihood or for what he and his family needs whilst they are learning on the farm, and then we take the rest. He puts in the labour; we put in the land, the kit and the working capital as required. I have an agreement with each that is a single sheet of A4 and which on its face states that it is not to be legally binding. We are not far off breaking even sometimes!

And thirdly, all the businesses operate under a common brand, Stream Farm. We all help each other whenever there is a need for more labour – as used to happen in villages once upon a time: to gut 100 fish, say, to lamb the ewes, to move the cattle whatever – and we all make sure that all our families are in good shape all the time as best we can. So we meet often and begin to learn again that sense of community that has been largely lost in the rural communities of England.

We go for excellence in all the produce and ensure that all of it meets very high quality standards. And we have been rewarded over the years, to our astonishment, by winning all the prizes, including Best Meat in Bristol for the last three years (for which the public vote) and gold for all our produce at the Taste of the West and some good stars at the Great Taste awards.

Hopefully we keep each other up to the mark – and, as with credit unions, we have a common bond, a shared interest, in our case our Christian faith that encourages us all to seek the best out of each other and out of each other’s businesses.

We all hope that the brand will begin to burn its way on to the national consciousness, as I said, and to spread to other farms and other landowners; we are hoping that politicians will spot it as a way forward that is worth investigating.

And then, who knows, there will be a need for more people again in farming, more young people to take on the businesses, more village houses needed for locals, the return of the pub and the post office and, dare I say it, the men’s outfitters that used to be in every village – more village schools, more life back in the rural communities. I am shameless about this: we need as many land owners and commentators and businesses as we can persuade to come alongside what we are doing – that old word ‘belonging’ comes from a root that means to walk alongside another person.

It is to create again a lost sense of belonging that Stream Farm exists.