THE LORD OF THE RINGS – by J R R Tolkien

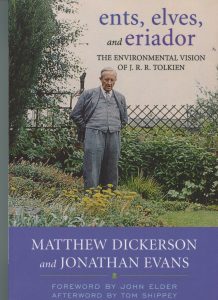

Critique of ENTS ELVES AND ERIADOR: The environmental vision of J R R Tolkien – by Mathew Dickerson and Jonathan Evans

Obtainable through Amazon

This is one of an occasional series by Alasdair Crosby , on books that might be considered to be ‘RURAL CLASSICS’

WHENEVER I am tempted to think about agricultural economics, I sit down in an armchair and read The Lord of the Rings until the fit passes.

I first read J R R Tolkien’s famous book when, as an impressionable 14-year-old, the three-volume hardback edition was given to me as a Christmas present. I have a vague recollection of a prolonged reading splurge: the whole book read almost in one go – several nights of sitting up in bed until the late small hours. Once finished, I started on it again.

My re-reading rate may have decreased significantly in more recent times, but even so, just to look at those same three faded red book covers – still in my bookcase – is to risk ‘the lure of the ring’ that tries regularly to drag me yet again into the alternative dimension of Tolkien’s Middle Earth.

I have, I suppose, a natural empathy with hobbits who ‘eat five meals a day when they can get them’. My wife is not such a Tolkien fan, but nevertheless she loyally accompanied me to watch the Peter Jackson films when they came out. After having sat through what seemed to her an interminable and, at times, a rather frightening sequence of battle scenes and orcs and screeching monsters, I will not repeat what she replied when I remarked to her, as we made our way out through the cinema’s foyer, that of course the film should have been longer.

By that I meant that the films, good as they are of their type, cannot compare with the books because, inevitably, they concentrate too much on the action and less on the background or on Tolkien’s implied philosophy. And the subsequent trilogy of films based very loosely on The Hobbit, could be any sword and sorcery epic set in any imaginary world.

There is, of course, the implicit Christian, specifically Catholic worldview that winds through the story of The Lord of the Rings, but leaving that aside (interesting though this subject is), another whole aspect of the work is the author’s equally implicit view of economics and the ideal society… and that is why nowadays I still frequently turn to it, rather than because necessarily I want to re-read the very familiar adventures with orcs or all those battle scenes yet again.

Why should the film have been longer? Apart from one or two scenes of the rural Shire home of Frodo and of the other hobbits that occur at the very beginning of the first of the film trilogy, there is no exposition of the nature of their homeland, as occurs in the book’s Prologue; also, the penultimate chapter of The Return of the King – the chapter titled The Scouring of the Shire – is omitted entirely.

These two sections, in my opinion, are the most interesting passages in the book.

The Shire, we read, had a distributive farming economy and produced, among other things, mushrooms, tobacco, turnips, apples and corn for cider and beer – all from family and small-scale agricultural enterprises.

There were also mills, markets, pubs, gardens and harvests. This is in contrast to the Narnia of C S Lewis, where apart from some brief mentions of hunting and an overgrown orchard, there is no description of where and how the food was produced; Narnian feasts, it seems, were liable to be produced magically with a shake of a mane.

Of course, the Shire was modelled partly on Tolkien’s nostalgically coloured remembrance of the rural Worcestershire of his childhood, in particular his home village. That nostalgia was strengthened by the village’s subsequent assimilation within the Birmingham conurbation – a triumph of the urban and industrial over the rural and the local.

In any case, Tolkien was a man who disliked modernity and all its trappings – evidently far happier in the world of Beowulf, he did not even drive a car. A good thing he did not live long enough to see the further advance of modernity towards and into the 21st Century: conversely one might speculate that his character, Saruman, who had ‘a mind of metal and wheels’ would have been delighted by the deceptions and lure of the Internet, I.T, the continued victory of urban development over the countryside, the present stage of evolution of globalism and free trade, tasteless ‘fast food’ and other unwelcome manifestations of the present age.

But the Shire was far more than a nostalgic rural idyll. It is a description of a viable agrarian society and how it might look and how it might work, the factors that could disrupt it and how otherwise it might last indefinitely. To quote from the book: ‘Ents, Elves and Eriador’ (one of the rapidly increasing ‘Tolkien studies’ genre) by Matthew Dickerson and Jonathan Evans (both of them American academics): ‘Tolkien explored how a cultivated, civilised, agrarian society might originate and how it might be managed in such a way as to exist for an extremely long time without jeopardising the health and productivity of its most important resource: the soil.’

The Dickerson and Evans book (from which all these quotes are taken) continues, itself quoting from the Prologue of TLOTR: ‘ “[Hobbits] have a close friendship with the earth” and “do not understand or like machines more complicated than a forge bellows, a water-mill or a hand-loom.” Hobbits disdain the sort of “progress” characterised in our own world by assembly-line manufacturing, industrial farming, advanced agricultural technology, agribusiness or the needless use of complex machinery when simpler tools will do. Hobbits are willing to use simple devices to further their farming techniques , but they do not employ technological innovations that might endanger the quality of the soil, water and air – the environmental sources on which their culture is directly dependent. In fact they are willing to sacrifice short-term convenience for greater long-term good….

‘…Apart from the immediate pleasures offered by work itself, their entertainments are the simple ones of food and drink, song and dance, long walks and hot baths, gossip and story-telling. Their agriculture – and thus their culture, is sustainable, presumably indefinitely.’

The Shire might be a wonderful place, but Tolkien lets us know that it is not a Utopia or a Paradise and hobbits are subject to the same temptations and moral failings as us ‘big folk’.

‘When Farmer Cotton describes the Shire’s troubles to the returning hobbits in ‘The Scouring of the Shire’, he explains his perception that ‘Pimple’ (Otho Sackville-Baggins) ‘owns “a sight more than was good for him”. In fact, Pimple has become a figure analogous to an agribusinessman in our own world. He does not merely own farms; he owns “plantations”. Furthermore, he exports the crops he grows. In this way, Pimple introduces into the Shire two problems: when those who work the land do not have a personal stake in its well-being, and when the food grown is not eaten by those growing it, attention to the practical virtues of agrarian life and work wanes.’

Tolkien’s solutions for the problems of maintaining a viable and long-lasting agrarian society are a statement of Distributism : the system of economy proposed earlier in the 20th Century by G K Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc, as an alternative to both capitalism and socialism. More modern proponents in this country have been E F Schumacher (author of ‘Small is Beautiful’). It is a diffuse economic system based upon small farmers, small business, and local trade.

To quote again from Dickerson & Evans: ‘The Shire embodies the Distributist economic vision. It is a rural community composed of farmers, craftsmen, and small businessmen, and its economy is based upon agrarianism. Many hobbits are gardeners or farmers. The only trade in which the Shire engages is based upon agricultural products such as the Shire’s famous pipeweed, though the hobbits only trade with outsiders after their own needs are met.

‘The two controlling powers of the modern industrial economy—big government and big business—are absent from the Shire. Bigness in any form is foreign to the Shire’s economy, which is localized, agricultural, and hobbit-sized in every sense.

‘After [the hobbits] leave on the quest to destroy the ring, the Shire’s economy changes dramatically. When the four hobbits return from their quest, big government and big business have encroached upon the former hobbit-sized economy, industrializing it. A large bureaucracy comprised of outsiders now controls the Shire’s economy, and its principles of production have expanded well beyond what is necessary simply for maintaining the needs of the Shire and its inhabitants.’

‘Most telling of the destruction of the Shire’s economy is the fate of Sandyman’s Mill. The new owners tear down the hobbit-sized mill and build a new industrial mill, which is run by wheels and contraptions and is powered by fire rather than water.’ (The former owner of the mill, Ted Sandyman, now works there as a paid employee).

‘The limited agricultural work that remains in the Shire is based upon an industrial system and “free trade” with surrounding communities. The formerly self-sufficient economy that was focused on localism and on providing what was needed to maintain its own citizens becomes a “global market” that seeks consumers outside its boundaries and leaves those within hungry.

‘When the four questing hobbits return to the Shire and discover what Sharkey has done, they lead the charge to restore the Shire’s rural-based economy. Though it will take years for the hobbits to undo the effects of industrialism, they set about at once to restore a Distributist economy in place of the modern industrial economy set up by Sharkey (Saruman).

‘They destroy the new mill and return the land to farmland and wooded areas. Private property is returned to its original owners, and the hobbits who had been employed in the factory-like mill return to their fields and their small crafts.

‘The redeemed Shire gives hope that a restoration to a Distributist economy is possible and shows that it is preferable to a modern industrial economy.

‘An agrarian society that is close to nature and experiences her natural ebb and flow has a greater respect for the environment than an industrial society, which emphasizes its independence from – and dominance over – nature.’

*Ents, Elves and Eriador, is published by the University of Kentucky, as one of a series titled ‘Culture of the Land – a series in the new Agrarianism.’

A short descriptive passage reads: ‘This series is devoted to the exploration and articulation of a new agrarianism that considers the health of habitats and human communities together. It is intended to demonstrate how agrarian insights and responsibilities can be worked out in diverse fields of learning and living: history, science, art, politics, economics, literature, philosophy, religion, urban planning, education, and public policy. Agrarianism is a comprehensive worldview that, appreciates the intimate and practical connections that exist between humans and the earth. It stands as our most promising alternative to the unsustainable and destructive ways of current global, industrial and consumer culture.’

The series editor is Norman Wirzba, and among the members of the advisory board are Wendell Berry, Michael Pollan and Vandana Shiva; the UK representative is Patrick Holden of the Sustainable Food Trust.