This presentation was delivered by the executive editor of Farmers Weekly, Philip Clarke

The subject of this presentation is a slightly risky task given that we still exist on shifting sands, both in terms of our future relationship with other countries and the future of domestic farm policy.

Having said that, we did have our own Farmers Weekly webinar just a few weeks ago, entitled What does the future of farming look like?, and having chaired and written that up for the magazine, I’m hopefully fairly up to speed with what’s going on.

I should also say at the start that I am really going to focus on the UK – my knowledge of agriculture on the island of Jersey is pretty limited.

WHERE ARE WE NOW AND WHERE ARE WE GOING?

I think I’ll start with a little look back.

There is no doubt that the farming sector in the UK is coming to the end of one of the most challenging years in living memory – although we do seem to say that rather a lot these days.

Farmers Weekly is currently conducting a survey of readers for a feature in our Christmas issue and one of the questions we asked was: ‘What has been the greatest challenge you have faced in 2020?’

The options given were: Coronavirus, market conditions, labour supply, extreme weather, rural crime, mental health, pests and disease, and government policy.

Without wishing to preempt the survey, I don’t doubt that we will find Covid-19 and government policy ranking high among the top challenges, together with the weather, of course.

On coronavirus – it was actually a pretty mixed picture. There was considerable market disruption in the early stages of lockdown, with breeding sheep and cattle sales suspended, some milk producers hit really hard by the closure of the food service sector, lamb prices tumbling. Farms with agrotourism and events diversifications were also hit hard in the early stages – though some benefited from a surge in business over the summer as many people opted for so-called ‘staycations’.

Others made good by selling more direct to the public.

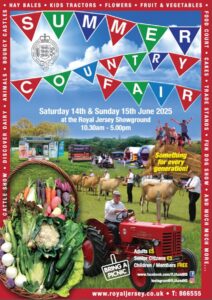

But there were also issues of increased pressure on the countryside, as the general public ventured out into rural areas more, with the attendant problems of sheep worrying, littering and rural crime. The long list of cancelled shows and events has also contributed to mental health challenges for some, and put some shows in real financial jeopardy.

Despite all the problems, however, the food and farming sector has probably fared better than many during the pandemic. After all, everybody still has to eat.

Turning now to farm policy – I don’t doubt that many of you will have been following the passage of the Agriculture Bill, which will set the framework for farm support in the years ahead.

The bill was actually brought back in January, following Boris Johnson’s victory in the general election, and contained a number of improvements from its earlier version – such as a commitment to review food security every five years, a determination to improve the farmer’s return from the supply chain, and the possibility of market intervention in the event of a crisis.

But it also set out the timetable for phasing out direct payments to farmers, starting as soon as next year, with cuts of 5% for first £30,000, climbing to 25% cuts on payments of over £150,000.

These cuts will continue until 2027, when the Basic Payments Scheme will cease to exist.

I know that Jersey farmers do not have anything like the same level of support as in the UK, but I’m sure you can all imagine the deep concern that exists when the BPS accounts for about 60% of farm profit.

It is some consolation that the total sum of taxpayer support for the sector is expected to remain the same for ‘the life of the current parliament’ – but after that is anybody’s guess, though it’s fairly safe to assume the sums will go down, not up.

We also know from the Agriculture Bill that payments will be ‘de-linked’ from a need to produce food, and there will be an opportunity for farmers to take future payments as a lump sum at the start of the seven-year transition period. This could either be used as an ‘outgoers’ payment to retire from farming, or could be used to invest in the farm to raise productivity, or even to diversify.

The other key element in all this is the government’s plans to introduce its ‘public money for public goods’ approach – primarily through the development of its Environmental Land Management or ELMs scheme.

This will reward farmers for helping to deliver things like clean air, reduced pollution, thriving wildlife, clean water, enhanced landscapes and measures to mitigate climate change.

Further details on ELMs are expected later this month, but based on a discussion document published earlier this year, it is known that the government is planning a three-tier approach, with a base level to encourage environmentally friendly farming, rising to a third tier for landscape scale projects such as peat restoration and forest creation.

A national pilot scheme is due to be launched next year, with the full scheme up and running from late 2024.

It’s not all about ELMs, of course. The Animal Health and Welfare Pathway is another important element of this ‘public money for public goods’ strategy, that could see farmers paid for doing things like cutting stocking rates in chickens or improving lameness in dairy cows.

Defra is also planning a series of productivity grants, to help farmers invest in equipment and technology.

I should add that much of what I’ve said so far is just in relation to England and English farming. Devolution adds another layer of complexity, though in general terms, administrations in Cardiff, Edinburgh and Belfast are looking to retain direct payments a little longer and to keep some kind of coupled support to encourage production in more challenging areas, though the move towards an environmental agenda is also on the way.

The other thing to talk about, of course, is the trade impact of Brexit, both with the EU and with the rest of the world.

You will no doubt be familiar with the political ping-pong between the House of Commons and the House of Lords over the Agriculture Bill, with the Lords keen to include a clause to make it illegal to import food which does not match up to UK food standards as part of any future free-trade deals, while the government is adamant that this is unnecessary.

Last Wednesday night the House of Commons voted in favour of a George Eustice amendment that will give MPs a bit more scrutiny of future trade deals, but again they rejected the notion of banning imports outright if they do not match UK standards.

To my mind, that is disappointing, as so many people care about the quality of their food – over 2.6 million people have now signed petitions saying they want such protection, yet the government refuses to enshrine it in primary legislation. Yes, ministers have said they will maintain high standards on imports – but ministers say lots of things, then fail to deliver.

So what are the prospects for trade deals?

Well, we are still waiting to hear the outcome of negotiations between the UK and Brussels on future arrangements for trade with the European Union.

In the middle of October it seemed like a ‘no-deal was the inevitable outcome, with Boris Johnson saying talks were off and to prepare for WTO terms of trade.

Yet, less than a week later, talks were back on… and they still are – just – with fisheries and state aids the main sticking points, as the UK seeks to maintain tariff-free access to the EU, while exercising as much ‘self-determination’ as possible.

The issue of Northern Ireland – though not so talked about in recent weeks – must also be a sticking point.

It is very clear that avoiding ‘no deal’ is in everyone’s interests. The UK sheep sector would be decimated if it had to pay tariffs of 46% on its exports, as would parts of the beef sector.

Having said that, as a net importer, prospects for the dairy sector are not quite so terrifying, as the imposition of tariffs could actually drive up prices in the UK market for butter and cheese, leading to better raw milk prices and a possible expansion of the dairy sector.

There would certainly be short-term volatility, as the supply chain adjusts. And there would be higher costs for things like labour, feed and fertiliser.

Much will also depend on the tariff level actually applied by the UK government to imports in the event of no-deal. There was some relief last May when it was revealed that dairy tariffs would not be cut, as had previously been suggested.

Similarly for potatoes, the UK remains a net importer and growers could benefit from a no-deal Brexit that pushes up prices, though there are other issues around the prospects for seed potato exports, should the UK fail to attain Third Country status in the event of a no-deal Brexit.

So, will there be a deal? I mentioned at the start our recent webinar on the What does the future of farming look like? The consensus there was that some kind of deal is still very likely. As one speaker put it: ‘I cannot imagine that Boris Johnson would agree to anything which will drive up the cost of food at a time when the economy is still reeling from the effects of Covid,’ – and I’m inclined to agree.

Furthermore, failure to secure a deal would undermine the government’s reputation for competence. The inevitable sight of lorries stacked up on the M26 in Kent and disruption to trade in general would bring the UK government back to the negotiating table fairly quickly in search of a deal they were pretending they could do without.

No-deal would also play into the hands of those in the devolved regions of the UK – especially in Scotland, where the SNP would capitalize on the impression of Westminster incompetence to further their quest for independence. It’s a risk Boris Johnson must be keen to avoid.

Time is clearly running out. Talks broke up again last Wednesday with both sides still reportedly far apart. It was originally said that a deal would have to be wrapped up by mid-October to allow the Brussels enough time to sign it off, but that has now become mid-November. The later it gets, the greater the chance of a ‘lightweight deal,’ rather than anything more comprehensive.

Turning now to future trade deals with the likes of the US, the perceived wisdom has been that, should the UK fail to get a decent deal with the EU, then the political importance of getting something done with America will be even greater.

There could be net gains for the whole UK economy – and even sheep producers and cheese producers could benefit from better market access to the US. But for a whole range of other agriculture commodities it spells danger – and there is no doubt that the powerful US agriculture lobby will be eager to secure full access to UK markets.

Of course, we have all been watching with open-mouthed amazement the most recent political developments in the US. It seems probable that we shall have a Biden presidency. The implications could be significant for the chances of the UK securing a free-trade deal with the US. Boris had a close relationship with Trump and there was a good chance they could meet the July deadline for ‘fast track’ legislation to approve a deal.

But Biden is reportedly more interested in forging trade deals with Berlin than with London. His Irish ancestry also mean he will not want to make it easy for the UK if the UK has done anything as part of its arrangements with the EU that could undermine the Good Friday Agreement.

As I said at the start, we are walking on shifting sands.

So, what is the future outlook for farming? How can it survive or even thrive in the face of such challenges?

One of the key things is that agriculture needs to become more outward looking. In our recent webinar, renowned economist Sean Rickard pointed out that, while UK demand for food is growing at just 0.7% a year, there is a massive, emerging global middle class. By 2030, there are expected to be 4bn people worldwide defined as ‘middle class’, and their food consumption is growing at 5% a year.

Just like the UK middle class who do their shopping at Waitrose, these people are also concerned with issues like food provenance, food safety and traceability – things that UK producers can deliver with their eyes shut. There are markets to be won out there, and not necessarily at rock bottom prices.

Yorkshire farmer George Fell makes similar comments in a recent issue of Farmers Weekly. Rather than obsessing about importing low-quality US beef and chicken, he argues more effort should be put into developing ‘brand Britain’.

But there will be more competition at home – especially as we seek out trade deals with other countries. The farming sector therefore needs to become more internationally competitive.

Yes, there are restrictions on what we can do, on the way we can operate. GM crops, for example, are banned and are likely to stay banned, and the prospect of being able to inject our beef cattle with oestrogen is non-existent – but there is also a great deal of upside in the way we can improve productivity.

A survey from a couple of years ago by AHDB showed the UK really lagging behind so many countries in terms of productivity growth, for example the Dutch have increased their “outputs to inputs” performance by 3% a year, compared with less than 1% in the UK.

The reasons are manifold, but irrelevant R&D and insufficient skills training are two of the key factors that need addressing. A mere 32% of English farmers have any formal training at all!

Addressing this will require an industry, a government and, above all, a personal commitment to raise the game. As stated earlier, there will be government grants available under the new domestic policy, but farmers need to become far more proactive when it comes to seeking out efficiencies.

Part of this can be achieved through greater collaboration. It sounds clichéd and the sector’s track record is not always so great, although there are plenty of success stories of farmers that have worked together to share equipment or set up profit-share arrangements. But I’m thinking more of collaboration along the food supply chain rather than just at the primary producer level.

It is surely no coincidence that in the dairy sector, the best milk prices in the league table we publish in Farmers Weekly are those to producers who are aligned to specific retailers. The same is true in other sectors like beef, horticulture, even cereals – where farmers who work with the food chain to deliver specific products for higher-end markets tend to get the best prices.

Next, we need to embrace technology. There may be a clash of interests here, with environmentalists and organic farmers advocating a move away from modern agricultural techniques towards more agroecology, which may be seen as being at odds with any push to more technological solutions. But that is not necessarily true.

Our recent webinar heard a lot about ‘sustainable intensification’ – the use of modern technology such as new breeding methods, precision farming and even the use of big data to drive production decisions. And by using the best land more productively, there will be more scope to allow more marginal land to be used for things like tree planting and habitat enrichment.

There are likely to be gains and losses in the future. For example, recent UK governments have been quite bullish in seeking to ban certain crop protection products like neonicotinoids and diquat, much to the frustration of commercial growers. But they are very keen on precision farming, and have been making warm noises around the subject of gene editing, where breaking free from Brussels could soon see this technology employed to the full, to deliver crops that are better yielding, more pest or drought tolerant, or even offer nutritional advantages to consumers.

Farmers also need to engage with ELMs. I can understand why there is a degree of scepticism, given the recent track record of agri-environment schemes to be overly complex and heavily audited. But sooner or later ELMs will be the only show in town and, whether farmers end up being paid for specific actions or for delivering particular results, that is where the support will be coming from.

Finally, it is inevitable that there will be continued consolidation as the industry looks for economies of scale. Sean Rickard has even mooted as many as a third of producers could exit the sector in the coming years – though Mr Rickard does like to make the headlines, it has to be said.

I understand that, in the last 20 years, the number of potato growers in Jersey had dropped from 150 to just 15. Similarly, when I first started working at the NFU in the mid-1980s on the milk committee, there were 37,000 dairy farmers in England and Wales. That figure now stands at 8,000.

So consolidation is a long-term trend, but I would not be at all surprised to see it accelerate again in the years ahead. Some farms will get bigger, while some of the smaller units will survive by diversifying or getting into niche production. But many will inevitably call it a day.

There is some cause for optimism, however. An AHDB paper published a couple of years ago showed that, whatever scenario they drew up for Brexit outcomes, the top 25% of farmers always made a profit. The trick, therefore, will be to get into that top 25% – though that is easier said than done!