The book, ‘The German Occupation of Jersey: Agriculture and Survival in a Time of War’ is by retired Jersey schoolmaster, Andrew Gilson. It is a very detailed account of how agriculture survived the Occupation, which, at this 80th anniversary of the Liberation, is appropriate to consider.

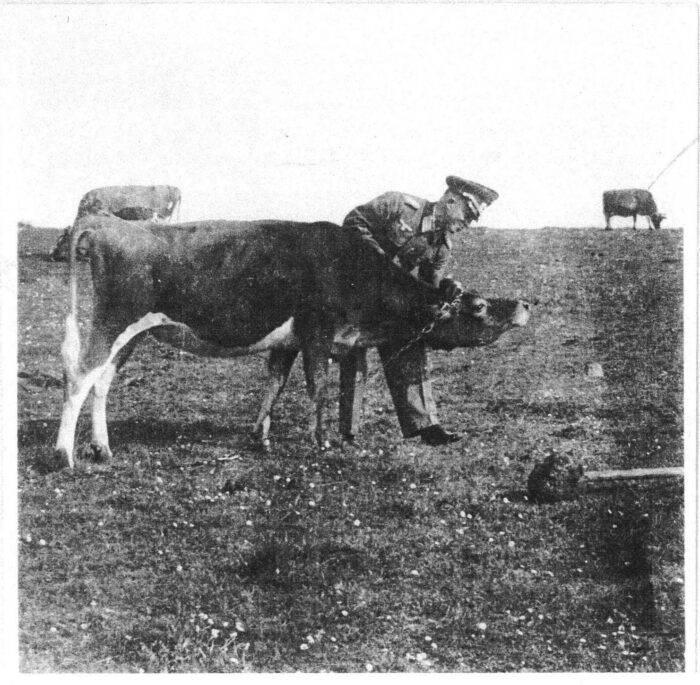

On 28 June 1940, the German Luftwaffe bombed Jersey— it resulted in many deaths and casualties. Earlier that morning, a pedigree calf was born at Seaview Farm, St Helier, and subsequently named by its owner, Jean Marie Le Flem, recorded in the Jersey Herd Book, as ‘Jersey Air Raid’.

Jean Marie, like all farmers, had to adapt immediately to the Occupation to survive the changed agricultural circumstances. Seaview Farm was 45 vergées. He farmed it with his two sons. The stock comprised of five Jersey cows, four pigs and one horse, called Tuppence. As the Occupation went on from year-to-year and the Germans were reluctant to provide extra petrol for agricultural machinery, working horses became a highly valued commodity.

Just over a month after the start of the Occupation, Major Hans Egon Pelz arrived in Jersey. He was head of the agriculture and food supplies section of the German Military Government, named Field Command 515. This was based at College House in Mont Millais, the former boarding and residential section of Victoria College (now the Jersey College for Girls).

Once in place, Field Command 515 comprised 200 members, experts in their relevant fields. These were bureaucrats in uniform as opposed to regular army personnel. The lower ranks were billeted in the Continental Hotel, St Saviour’s Road; the Staff Officers in spacious houses around the Island.

It seems like a huge number of people to govern such a small island (but a cynic might suggest that in that respect at least, nothing has changed too much in the decades following Liberation). Also, the quality and intellectual acuity of its members was most impressive. They included international lawyers, trained administrators, PhD level academics … Why had they all been sent to Jersey?

The answer is contained in the book ‘The German Occupation of Jersey: Agriculture and Survival in a Time of War’ by Andrew Gilson. It is a very detailed account of how agriculture survived the Occupation, which, at this 80th anniversary of the Occupation, is appropriate to consider. It will doubtless be the seminal work on this subject and it is an invaluable source of material for commentators and historians.

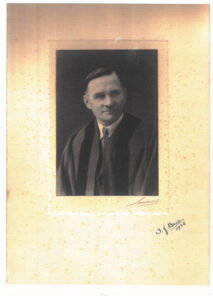

Andrew was a school master in Jersey for 36 years, retiring in 2014 as Head of History at Victoria College.

The book is some 17 chapters and comprises 200,000 words, original unpublished photos, maps, letters and diagrams. Topics covered include the dislocation of the 1940 potato and tomato harvests, new cropping plans, the changeover from a cash crop economy to a States regulated system of agricultural inputs and outputs: pigs, cattle and milk control, the rejuvenation of the Island’s water mills under the direction of the Department of Agriculture and new forms of agriculture. A detailed description is given of the increasing German demands for meat, milk and produce, the agricultural black market, the issue of collaboration, and the nature of the relationships between the leading German bureaucrats, the Superior Council, the Department of Agriculture and farmers.

In Andrew’s words: ‘When I read Pelz’s family biography, written by a daughter-in-law, it said quite clearly that Field Command 515 was going to be made ready to be sent to England straight after a successful Operation Sealion – the invasion of England. 515 were going to be the first German government administrative unit in occupied London. Field Command 515 was destined to go to London and be knocking on the doors of Westminster. Of course, plans for Operation Sealion were subsequently abandoned.’

Before the war, Pelz, who came from Salzburg, had a degree in agriculture, after which he worked in Salzburg as a cattle inspector and organised cross breeding and a herd book. He was sent to Jersey to oversee the Island’s pedigree herds and he was instrumental in the requisitioning of Jersey cattle for the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Germany.

For the system to work, there needed to be ‘collaboration’ (in the professional sense) all along the line. A German staff officer wrote about ‘ghosts and prostitutes’: in his eyes, the Jersey civil population as a whole either wanted to have nothing to do with the German administrators or else they stuck as closely to them as ladies of the night.

In fact, the personal relationships that were built up over five years with the German Military Government were much more nuanced. The chain of command

depended on personal relationships and it worked very well. There were many different types of relationships between the occupiers and the occupied.

The relationship between the Islanders and the Germans varied, there were very many shades; there were friendships, some of them very close friendships that may have edged into collaboration.

Fortunately both Pelz and the head of the Department of Agriculture, Jurat Touzel John Brée, were both practical and intelligent men. Brée was a successful, talented and hard-working farmer and Pelz had a farming background; they got on and worked together very well. As an illustration, for Christmas 1940 Brée gave Pelz an alarm clock – Pelz had a habit of turning up late for meetings!

They needed to meet up frequently to discuss problems in detail: mainly, the nationalisation of Jersey agriculture and the importation of continental cattle into Jersey. Before the war, agriculture was export-led, but after the Occupation had begun, that – of course – had to change completely.

The system had to be nationalised to provide home grown food for the Island population of 40,000 souls, and also for the German garrison, because, under the Hague Convention, the Germans were quite within their rights to requisition food, as well as to import French and foreign cattle into the Island.

Brée was informed by Pelz that they had to grow arable crops – wheat, barley, rye, oats – to produce home grown flour. By November 1940 old mills were back in use, under the auspices of the Department of Agriculture, to mill flour for bread. The Agriculture department told farmers what to grow so that all vegetable and cereal crops could be distributed as equitably as possible among the population, and so that the Germans could have their fair share.

Throughout the system there were checks and double checks: milk, potato and grain control, cattle and pig control. Given the circumstances of enemy Occupation, the system worked very well – at least until October 1944, when Pelz was posted to active service in mainland Europe and the status of Field Command 515 was reduced in size to a smaller version of an administrative unit, a Platzkommand.

The one common farming problem throughout the Occupation was labour. There was a real shortage of agricultural labourers which seems almost perverse, as there were some 1,500 men unemployed.

The subject of black marketeering is often raised in relation to the Occupation agricultural economy. There were some 1,800 farmers in the Island, but the quantity of black marketeering was, in fact, very small, unlike in France, where 20% of agricultural produce went through the black market.

It did happen – Jersey farmers sold produce to the Germans when Pelz signed an authorisation docket on behalf of 515. The authorisation docket stipulated the name of the farmer and the exact purchase details, and this was shown to the farmer. Therefore, why break the agricultural laws selling on the black market and risk ending up in the Royal Court? Brée gave transgressors a verbal warning and that was very effective with most miscreant farmers. Only extreme cases were prosecuted.

And how did the Le Flem family cope? They worked the farm without other labour. There was no tractor, only Tuppence, their horse, who remained with them throughout the Occupation. As farmers of the time put it clearly: ‘The horse saved Jersey during the Occupation’ and ‘they were worth more than a Rolls-Royce’.

All work was manual using sickles and scythes. Wheat and oats were tied, bundled, and stacked. When threshing took place, a group of four of five fellow farmers would arrive to help.

By 1943 the entire agricultural process began to hit major problems as inputs became scarce and the Germans were making increasing demands for extra produce. Jean Marie grew tobacco under licence, as all farmers did. The crop was planted in May and harvested in August. Each plant was taken out of the soil and each leaf was stripped individually before being dried and cured in the loft. Tobacco became an increasingly important cash crop as the Occupation progressed. It could be sold, used as a form of barter or even payment for goods. German soldiers were happy to exchange goods and purchase tobacco from farmers.

By the end of 1943 a new problem hit Jersey farmers, that of crop security. Jean’s two boys slept every night fully clothed, armed with pickaxe handles and two dogs with which they would chase people attempting to steal crops.

1944 found the family with another problem, that of trying to help desperate townspeople with obtaining produce. The Le Flem family allowed them to collect the grain left on the fields after harvesting and threshing.

Jean Marie’s son, Dennis, found himself in a potentially dangerous situation when he was caught by the Germans ferreting without a licence. Along with his ferret, Joey, he was taken to College House and spoken to by a German officer. Dennis had to pay a 30 Reichsmark fine and hand over Joey to the German, who immediately received a vicious bite from the animal! Served him right!

It is worthwhile recording that the quality of the cattle straight after the Occupation was fantastic, because the ‘bad’ cows, heifers and milkers, had been turned into meat. Also, everybody in Jersey – not just children – received full fat milk for the entire Occupation. Jersey was the only occupied area in Europe where this happened.

The author concludes that serious collaboration can be ruled out. There were structural relationships built up through having to work together (the German Military Government and the Superior Council) in order that the Island and military population was fed.

The book, priced at £30, is available at the Royal Jersey Showground, Waterstones, Amazon, or, for signed copies, from the author at aggilson99@gmail.com

The article was first published in the Jersey Evening Post, and is reprinted here with their kind permission