ONCE upon a time, there was an island in the west where apples grew. But this island lay not in the fables of Celtic or Greek mythology; this was a real island in the midst of the cold and salty waters of the English Channel. Jersey was an isle of apples and apple trees.

Apple trees have, in fact, helped to shape Jersey’s traditional landscape of little fields protected by hedges surmounting high banks. Maps of town in the early 19th Century, before it began to expand out of its historic confines, show that where there are now streets and houses once stood hundreds and hundreds of apple trees.

An elderly lady – now long deceased – once recollected her first visit to the Island in the springtime of 1925. She stepped off the mailboat and was met by her friends on the pier with a pony and trap. They clip-clopped off home, into the countryside, and as they drove through the lanes the apple blossom in the orchards was so thick that the scent filled the air.

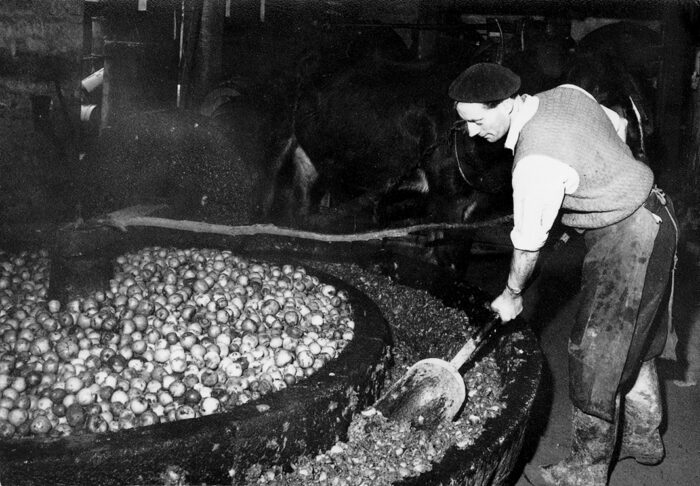

Those days are long past now. Even then, there were far fewer orchards than there had been in a few decades before. Orchards had been grubbed up to make space, first for outside tomatoes, then for the Jersey Royal potato. The stone apple crushers once used in farms all over the Island have since become largely decorative surrounds for flower beds.

Cider, of no great quality, continued to be made for Breton farm labourers for as long as they continued to work in the Island, but Portuguese workers, on the whole, preferred wine or beer and the cider production diminished to almost zero.

But the important word there is ‘almost’, because cider production never quite stopped altogether, and now it looks as if something of a renaissance in cider apple growing is taking place.

With due respect to the Island’s Jersey Royal growers, the sight of apple blossom, or of apple trees laden with fruit, has a picturesque quality to it that plastic sheeting over fields of young potato plants doesn’t quite match.

The Jersey cider apple has had a distinguished past before its decline and fall; now, in the 21st Century there have been more orchards grown and more cider made than for many a long year.

PROMINENT among present owners of apple orchards is Vincent Obbard, owner of Samarès Manor and president of the Jersey Cider Orchard Trust.

‘There was a very big orchard at Samarès , that I think was planted in the 1680s, probably with over 1,000 trees. There must have been a huge workforce in that unmechanised era. The Seigneur of Samarès at the time, Philippe Dumaresq, probably paid them at least partly in cider. His men did an enormous amount of work; they drained the land to create gardens around the manor and they dug the canal that runs from the Manor to Le Dicq. ‘

In more modern times, in about 1930, the then Seigneur and owner of Samarès Manor, Sir James Knott, planted an orchard behind the manor with perhaps 100 different English apple varieties and some pear varieties. It was cut down in about 1960.

‘The apples never got pruned, and they were full of disease. Nobody knew what they were, cows nibbled the bark of the old trees and it would have been too labour intensive to maintain.’

But Samarès is a prime spot for orchards. The area was covered with cider orchards in the past, in the same way that nowadays it is covered by building development.

‘There was a huge old orchard that used to extend from La Blinerie (the lane behind the manor) to the St Clement Inner Road. Looking at old maps, Samarès was absolutely plastered with apple trees. They must have made thousands of gallons of cider.’

By the 20th Century, cider production had declined in Jersey. During the Occupation, there was a slight revival in growing apples and making cider. But after the Liberation, more orchards were turned over to the potato.

The storm of 1947 uprooted many apple trees. By the late 1960s there were just 173 vergées of orchard in Jersey. The great storm of October 1987 caused more loss of ancient varieties of Jersey’s cider apples. Amid growing concern for the future of the Island heritage of local apple varieties, a nursery with 150 rootstocks was created in 1989.

Jurat Henry Perrée, who was secretary of the National Trust at the time, collected graft-wood from several known varieties and gave the wood to a nurseryman to be grafted on to rootstocks for standard trees.

During 1988 to 1998, at least 350 trees were examined, of which 172 were officially numbered, tagged and recorded. The naming proved very difficult as even the experts were not familiar with more than a handful of the old varieties and historical records barely mentioned the names.

Orchards were planted in the 1990s, and an extensive orchard was planted at The Elms (National Trust for Jersey) in 2003 to preserve apple varieties as a gene bank.

The Société Jersiaise and National Trust for Jersey formed ‘The Jersey Cider Orchard Trust’ (JCOT) in 2002, led by the late Brian Phillipps and Rosemary Bett, with the aim of locating, identifying and preserving local apple varieties. Together, they did much to save the Jersey Cider apple from extinction. .

There is now considerable interest in the Jersey cider apple, with several requests to JCOT for advice on planting orchards or small collections.

Other orchards have since been planted, many of them thanks to the enthusiasm and energy of Brian Phillipps and Rosemary Bett.

Brian thought it would be a good idea to plant new orchards in the land belonging to Samarès Manor.

‘Brian was such an enthusiast,’ Vincent remembered. ‘ You couldn’t stop him. He couldn’t help doing what he thought had to done, to rescue all these old varieties. He felt it was a task worth undertaking – and it was a mammoth task, absolutely huge.

‘He worked so hard, grafting and planting them. Thanks largely to him and to Rosemary Bett, a collection of Jersey varietal apple trees was established. Guernsey didn’t do it, and they have lost all of their varieties.

‘The Jersey collection compares so brilliantly with collections elsewhere. There are more Jersey apple varieties that have been collected than in the whole of Scotland or the whole of Wales. It puts the Island on the map. But it couldn’t have been done without a whole lot of work that Brian did.’

Vincent continued: ‘I had a visit from Brian some time in the early 1990s. He told me: “You should have an orchard!” He didn’t know me at all, really, but he had this idea that this was the perfect place for one. The idea attracted me: for one thing, I had a bit of a guilt complex after having destroyed the old tumbledown orchard, for another, I was just interested in creating a new one. Together, we created a big orchard in 1995.’

At present, JCOT has around 22 members. Subscriptions are very low: £5 a year, and the annual general meetings are always more fun than the average agm, with plenty of tasting of members’ home-made ciders. This year, the trust had a stand at ‘La Faîs’sie d’Cidre’ event at Hamptonne.

‘It was a great day out, with lovely weather, — at least on the Saturday. It was a lovely atmosphere.

What did he think the future held for Jersey cider?

‘Apple trees grow very easily and they are very popular with rich residents who want to screen their property or who don’t want to let their land out to the potato industry, with its attendant noise, dust, and spraying at different times of the year. But it has to be let to a bona fide farmer, and they are allowed, under the terms of their purchase, to plant apple trees. So, there are a lot of apple trees planted, which usually are not picked. It is a bit sad… I’ve no idea which varieties are most commonly planted. I suspect that they come mostly from France.’

This year, there has been a glut of apples, as anybody who has been in an orchard and trodden over a carpet of windfalls, or driven along a lane and seen the containers of apples along the sides of roads, free for collection with little or no payment requested.

‘It is a terrible waste,’ Vincent said, ‘and we need someone to make cider commercially from our Jersey varieties. It would give the whole idea of growing Jersey apple trees a real purpose.’

CERTAINLY, if there is any redundant land, a good answer to the question of what to do with it is to put it under apple trees. It would be good for the environment, it certainly would not harm the land, and if at any time the land was need for something showing a more immediate return, it could be almost immediately available.

There could be other benefits, not least that visitors would want to come to see an Island covered with apple blossom. The ecology would benefit and it could encourage more people to try their hand at farming on a small scale.

And what could be more attractive than an Island covered with apple orchards?

The big apple in Jersey – Jersey’s once and future crop? Unfortunately, it’s more likely is that the warm glow of the fire under the bachin at Black Butter time is only the glow of a nostalgia for a rural past.

- For more information about membership of JCOT, contact the trust’s secretary, Dom Hodnett at quereehodnett@gmail.com or Vincent Obbard at vincentobbard@gmail.com